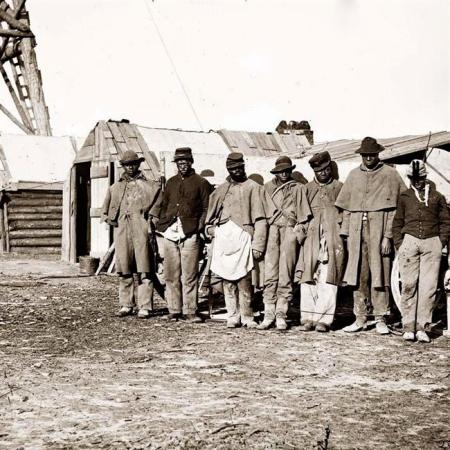

“I regret to inform you that I found the place [St. Augustine] full of open and avowed traitors. I was insulted in the streets by secession females. I learned that there were women residing there whose husbands are in the rebel service, and who are receiving rations from our Government. Seventy-five slaves are receiving wages from our people, who are owned by rebel masters, and their wages are paid over to the agents of these masters.

Courtesy of Southern Methodist University, DeGolyer Library

[Recounting an incident involving a slave handed over to his ‘master’ in Florida]: While I was in St. Augustine, I was informed…that a fugitive slave who ran away from his rebel master—a man named Col. Titus (of Kansas notoriety)* and who holds a commission in the rebel army—was delivered up to said Titus by virtue of an order signed by Capt. Foster [in] circumstances…so disgraceful to our army that I felt it my duty to report them. This negro came to our lines from his rebel master heavily [wounded], having traveled a distance of eight miles in this condition to our pickets. He remained with our troops until [Titus] came with an order signed by Capt. Foster…directing Col. Sleeper to deliver him to his owner. He was delivered to Col. Titus. On receiving this negro Col. Titus put a slipping noose rope around the negro’s neck, with a timber pitch at his arm, mounted his horse and dragged the poor victim off in the presence of our troops….

On the day of my arrival [at St Simon’s Island, Georgia] a party of rebels came over to the island for the purpose of murdering the negroes. They were immediately attacked by the negro pickets and surrounded in a swamp. There were about twenty men on either side, and quite a brisk action occurred. The negroes lost two killed and one wounded severely. The rebel loss is not known, as they fled, and succeeded in making their escape from the island….”

General Rufus B. Saxton to Edwin M. Stanton, 20 Aug 1862, Rufus and S. Willard Saxton Papers, Sterling Memorial Library: Yale University

* Colonel Henry T. Titus (after whom the town of Titusville, Florida, is named) was a northern-born Confederate who before the war had traveled to Kansas to join proslavery ‘border ruffians’ there, playing a prominent role in the sacking of Lawrence and at one point reportedly holding two of John Brown’s sons as prisoners.